Boston: The Illuminated City

Written by Victorian Solan

Consultant Historian for GLOW

When walking around the Rose Kennedy Greenway, or indeed any part of Boston in the evening, it is easy to take our cheap and plentiful electric light for granted. Different forms of artificial illumination compete for our attention: pedestrian signals flash, signs advertise our destination, and sidewalks and public spaces are well lit enough for most of us to navigate the night with relative ease and comfort. Yet it was not always this way. The urban lights we take for granted today grew incrementally, using multiple fuels and forms of technology.

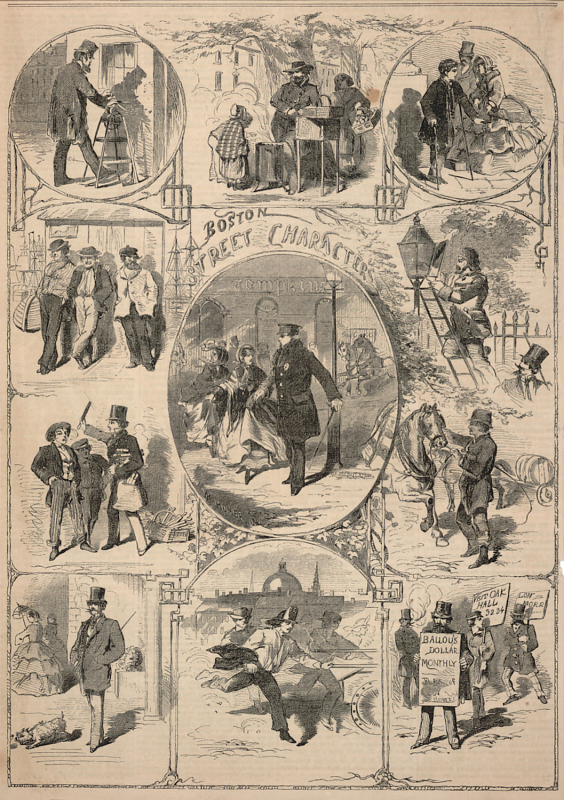

In 1630, when Boston was founded, nighttime security was a primary concern for its citizens. The dark streets of the 17th century city were seen as an invitation to crime and accidents. Curfew laws and the cost of lamp oil kept most Bostonian indoors at night. In 1635, the city established its first night watch patrol: two men were hired and charged with the duty of walking the city’s narrow, uneven streets, looking out for fires or criminal activity.

Despite being a major center for lamp oil production, Boston resisted installing public street lamps until 1774, when the city ordered 300 lamps from London. This first batch of public streetlights was long overdue, but unfortunately incurred vandalism at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War and were removed for safe storage. Throughout the eighteenth century, outdoor lighting was largely a personal affair: citizens carried lamps when they needed to go out at night. Night-time activities were limited, even for those wealthy enough to afford lamp oil.

The invention of inexpensive gas lamps changed the city, both indoors and out. Factories were typically among the first purchasers of gas lighting. Seth Bemis, a Watertown cotton merchant, illuminated his factory with the new lights as early as 1813. Private customers, both business and domestic, drove the demand for gas lines to be piped through specific streets and neighborhoods; public lighting gradually followed the installation of gas lines. The first public gas lamp, installed at Dock Square in 1829, was not far from the current site of the Greenway’s GLOW exhibition. Although gas light was not as bright as modern electric and required daily maintenance; it offered an indication of the future. No longer did work need to cease at sunset: longer hours and regular schedules meant greater wealth for factory owners and storekeepers, and, to a lesser extent, their employees. Commercial night life as we now know it emerged with downtown amusements like Washington Gardens and other venues serving drinks, dancing, and entertainment well into the night. Gas light and the wages of its routines set the stage for modern life in Boston.

Electric light, even cheaper and brighter than gas, was first displayed in Boston in 1878. Merchants quickly capitalized on the clean, white light which drew shoppers to their windows and customers to their restaurants. By the 1880s, electric light had established a firm footing in Boston, and the cityhad drawn up provisional contracts for public lighting with four private companies. Boston’s first electric street lights were placed primarily along commercial, rather than residential streets. Storekeepers welcomed the attention which public lighting brought to retail areas. Restaurants and beer gardens bloomed as the city became simply easier to navigate after dark. Dorchester-born painter Childe Hassam captured the distinctive atmosphere of early artificial lighting in Boston in his well-known painting, “At Dusk (Boston Common at Twilight)” of 1885-6. The painting, which is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, shows the magic of street lamps twinkling against darkening buildings at the end of the day. This scene lays the groundwork for the fully-illuminated city we use today: a world of neon, LED, and other brilliant technologies.

Sources: Anne Beamish, “Rendering the Darkness Visible: Boston at Night,” in Sandy Isenstadt; Margaret Maile Petty and Dietrich Neumann, eds., Cities of Light: Two Centuries of Urban Illumination, (New York: Routledge, 2015); A. Roger Ekirch, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005).