Pouncing: History, Context, and Practice on The Greenway

Written by Sophie Pollock, Greenway Conservancy 2022 Tisch Summer Fellow

The current mural at Dewey Square on The Greenway, BREATHE LIFE TOGETHER, was entirely hand painted by a dedicated team of artists between May 1 and June 25, 2022. In the following article, I share my personal experience helping actualize this beautiful piece, in addition to parts of a conversation I had with a couple of the most active contributors to Boston’s public art scene.

I learned about pouncing during my first week at the Greenway Conservancy, when I decided to tag along to an informal introduction to the technique with some members of the GN Crew. Representing the Crew was TakeOne, Soem, and GoFive. An achingly talented group of Bostonian aerosol artists and muralists, they are also close friends of ProBlak’s (also in the Crew) who personally requested their assistance in helping make the mural. While they may well be some of the most kind-hearted and funny people I’ve ever met, this group couldn’t be more serious about art. Around the GN Crew, I couldn’t help but feel like a wide-eyed apprentice surrounded by true masters of their craft.

But before any actual painting happened on BREATHE LIFE TOGETHER, it was necessary to outline ProBlak’s design on the wall at Dewey Square (formally known as the Dewey Square Tunnel Air Intake Structure). In addition to its impressive size, the wall afforded by this unique structure is composed of multiple materials and some peculiar painting surfaces, including doors and lamps. Other reliable forms of pre-painting image outlining (like projecting) were off the table—pouncing, which was new to everyone in the Crew, was the only way to go.

Myself, the Crew, and my incredible supervisor Dr. Lopez all met in Jamaica Plain to study the technique with Boston’s very own Best Dressed Signs. The founders, Josh Luke and Meredith Kasabian, are completely dedicated to the craft of hand-painted signs, custom lettering, and murals. Not only do they run Best Dressed Signs together—Luke and Kasabian also curate and participate in gallery shows, conduct painting demonstrations, and give lectures on the historical and cultural contexts of signs.

At this point in Boston, it was, unfortunately, still cold outside. Yet there’s something about the city’s firm clear sky and steady brightness that, when combined with some sporadic gusts of Arctic air, might genuinely be “refreshing”—an intentional word choice, as I’ve discovered that many New Englanders like to reframe what most might consider to be a bitter, unforgiving outdoor experience in these terms. Euphemisms aside, I already felt warm and welcomed by everyone within that first week. While I mentioned the Crew is deeply serious about art, it must be emphasized that there was nothing cold or distant about their seriousness. In fact, they encouraged me to ask questions, were devout in their patience with me, and gave me some of the most impactful artist-to-artist advice I’ve yet to receive. This speaks to their commitment to seeing the arts scene in Boston blossom by sharing the wealth of their extensive knowledge, reflected in their long standing work as mentors to creative youth across the city. Combined with a general open-mindedness from all parties involved, this standard of collective care made me feel like I belonged, both creatively and personally, for the first time since I finished up school in December.

Pouncing is a centuries-old image transferring method that in my experience exists relatively unbeknownst to the general public. While its name comes from an old English term for tattooing from before the eighteenth century, pouncing’s reliability as a process means it is still utilized today by painters, ceramicists, muralists, and more. It’s an operation that is crucial in ensuring final artworks adhere to an artist’s original vision, and as such, I quickly became invested in learning more about pouncing—from its historical background to how it’s used today by contemporary artists.

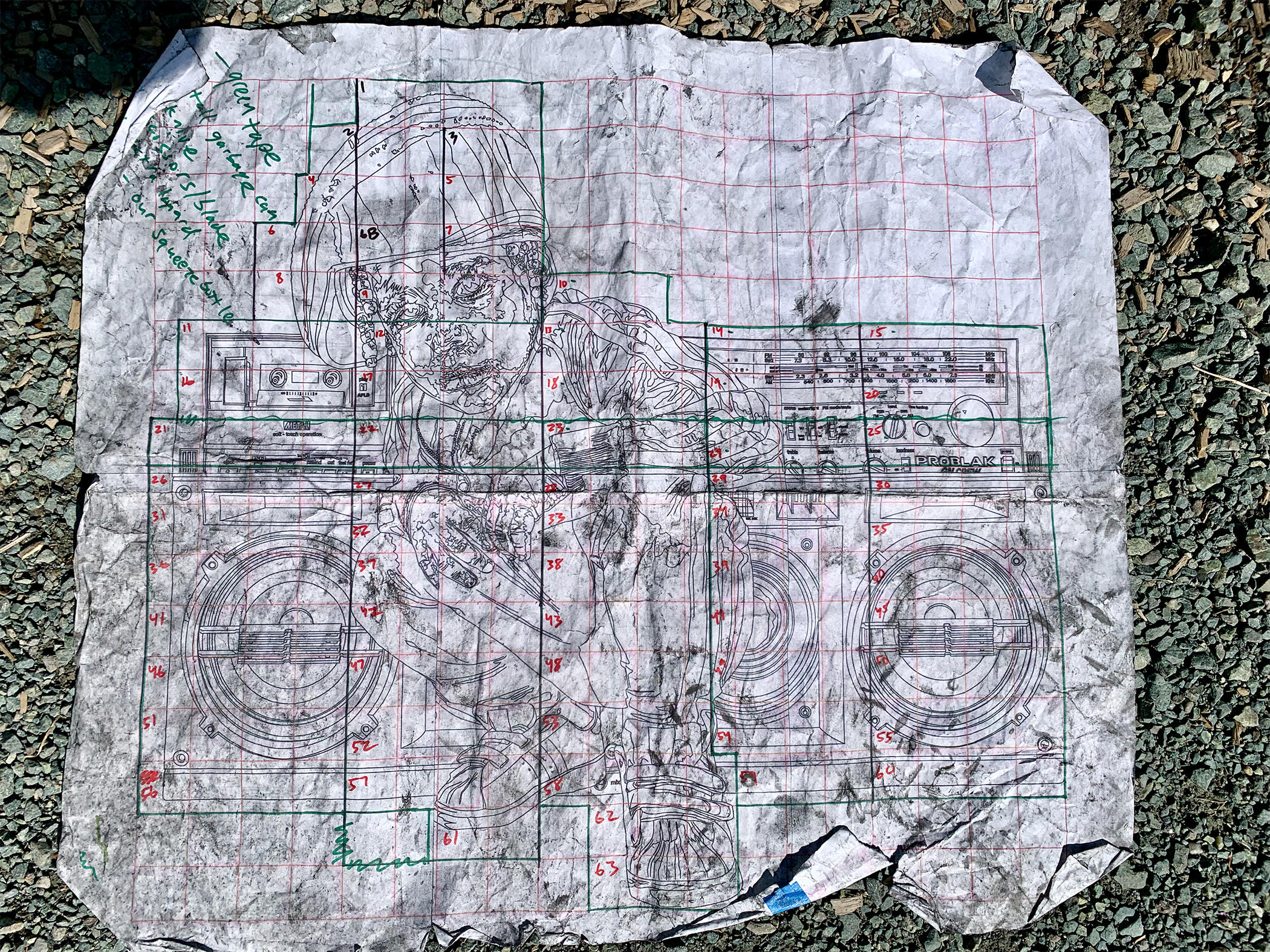

Guide sheet for pouncing BREATHE LIFE TOGETHER. Each number corresponds to a different pattern, which, when temporarily taped to the wall and pounced with charcoal, left dotted lines for the GN Crew to go over with spray paint. Photo: Courtesy of Best Dressed Signs.

“Pouncing is a technique used to transfer an image from paper onto a wall or other surface by pressing chalk or charcoal through perforated lines in the paper,” Luke and Kasabian said. “Often, the image is scaled up from a small drawing or digital image and is either drawn to scale using a projector or printed onto large paper.”

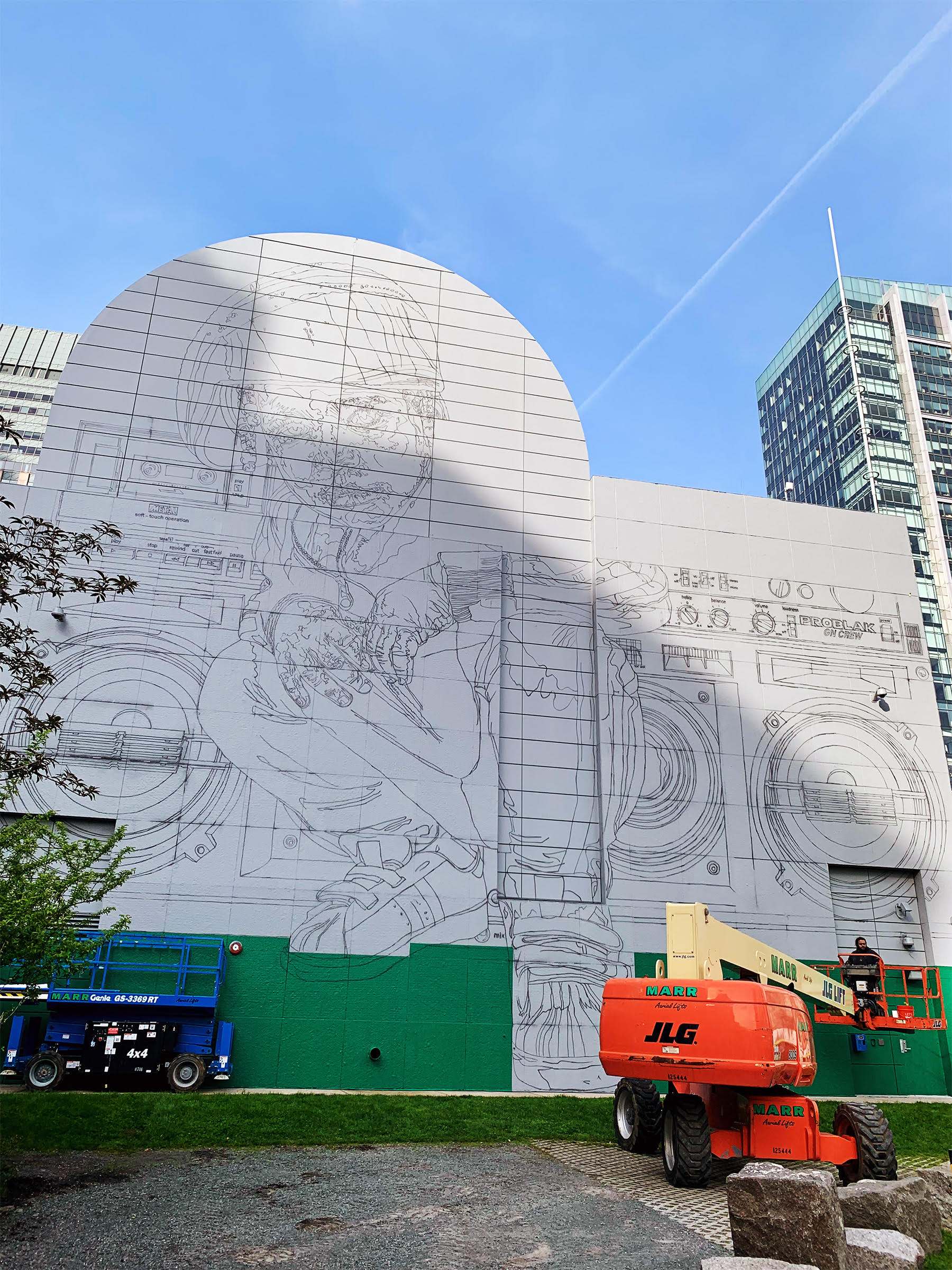

During the early stages of creating the mural, sometime in early May, I was fortunate enough to help the GN Crew and Best Dressed Signs pounce the upper portion of the figure’s outline and some text on the boombox. Still feeling giddy about my brand-new certification to operate two different kinds of industrial lifts, which I received during my first week at the Greenway Conservancy (and still have tucked away in my wallet…you know, just in case) I got a call from GoFive asking if I was available to help assist with pouncing the wall at Dewey Square.

Of course, there was no question that I’d be there. I packed up my small blue backpack in a frenzied excitement, feeling relieved that I had decided to wear all-black that day. But as I walked to the mural, I felt the subtle weight of a pit developing in my stomach. You notice the wind differently when you’re making your way towards heavy machinery waiting to whisk you 65-feet up in the air. The pit was starting to crack and blossom, generating jolts of nervous energy that began to gather in my throat. I burst into a jog, submitting myself to the most mild form of public humiliation, watching puffs of breath rhythmically exist-then-vanish through the inky frame of my oversized Boiler Room sweatshirt. The last thing I wanted to be was cold—I needed full finger and toe mobility for my upcoming task, and at this point I didn’t have the mental capacity to start reframing anything as refreshing.

When I made it to Dewey Square, Luke of Best Dressed Signs walked me through what areas we were going to be working on. He rolled out a large piece of paper with the mural design on it, pointing back and forth between the paper and the wall. I quickly learned this paper, called a guide, was very important—it was tenderly numbered to show us where the sheets of pre-punched paper (also known as patterns) should go on the wall. By the time I arrived, the guide was already blessed with copious amounts of charcoal and spray paint. I gave myself another mental pat-on-the-back for wearing black…then I put on my harness, helped load the lift, locked in, and went up!

While I had been battling my gentle shivers with nervous pacing and jumping jacks on the lawn at Dewey, all of my weather-related concerns disappeared the moment we ascended upward. The combination of my own adrenaline and the heat of the springtime sun reflecting against the mural wall extracted the know-how out of me. I felt focused.

To create the patterns for pouncing, ProBlak sent TakeOne a photo of his original mural design, which he then converted to a vector file and resized digitally to be as big as the wall. (It’s imperative to have a vectorized image if you know you’ll ultimately need it to exist life-size, since vector images won’t pixelate no matter how large you blow them up.) Once in the inbox of Best Dressed Signs, they carefully chopped up ProBlak’s design (still digital at this point) into 64 individually numbered sheets of what would soon be printed as massive pieces of paper. Then, the to-scale papers underwent the perforation process. It can be done with something as simple as a push pin, but as you might imagine, most large-scale works require something more precise. Technology such as an electro-pounce machine burns holes into the paper using an electrical current, while plotter printers punch holes in the paper whilst “printing” the digitized, vectorized image.

“The pattern is brought to the site where the painting will be done, taped onto the surface, and then ‘pounced’ with chalk or charcoal, which pushes through the perforated holes to transfer the image to the wall. The pattern paper is removed, leaving the chalk outlines as a guide for the painting,” Luke and Kasabian explain.

At this point on the lift, Luke began to tape up the pattern with efficient precision, while Soem and I alternated refilling the pounce pads with powdered charcoal, ripping off pieces of tape from the roll for easy access, and helping keep the pattern level on the wall. Once everything was in place, each of us grabbed a pounce pad and began generously smacking the pattern on the wall in a dusty percussion, leaving faint dots for the Crew to later connect with smooth lines of spray paint.

Wall at Dewey Square with outlines done in aerosol paint over the charcoal pounce lines. Photo: Courtesy of Best Dressed Signs.

Although officially introduced to pouncing in 2005 when he began his sign painting career at New Bohemia Signs, Luke had actually heard of the technique a few years earlier while in art school studying Renaissance painters. Back then, it was particularly useful for artists painting on irregular surfaces, such as chapel ceilings—by using the pouncing technique, drawings (including the one below) could be transformed into intricate paintings which decorated frescoes and more.

Putti Playing with Hoops (Cartoon for a Fresco in the Parma Cathedral), Michelangelo Anselmi (Italian, Siena or Lucca (?) 1492–1556 Parma), Black chalk; outlines pricked for transfer.

After working together on the lift for a while, there came a natural time for the three of us to descend back to Dewey to grab more patterns and to take a quick break on solid ground. This isn’t the kind of work you can do once the sun sets—every second of daylight counts, so it’s important to move quickly and efficiently, which is even easier to do so once you’re in a groove with those you’re on the lift with. I like to think we had a pretty good groove going, which resulted in me completely losing track of time.

When I was finally reunited with my phone, I caught my reflection on my unopened lock screen. A smile leaked its way out of my mind and started to trickle across my lips. I was highly aware of the status of my dusty fingers after taking off my gloves, but nothing could have prepared me for the amount of charcoal smeared all over my face. I started laughing and sent a selfie to my mom, which felt like the right thing to do. Then I realized it was past 5:00 p.m., which meant I had to go home.

I reluctantly replaced my harness with my backpack and said my goodbyes to Soem, GoFive, TakeOne, and Luke. An unidentifiable white, slightly greasy pastry box near our belongings was actually filled to the brim with a feast of sweet treats gifted to us by a friend of the Crew’s while we were working. I could never deny myself the pleasure of a big, soft chocolate chip cookie, and its reliable sweetness grounded me after a day spent up in the air. I strolled back to the office this time, feeling both weightless and oh-so full.

Looking back, one of the most meaningful parts of learning the pouncing technique all together with Best Dressed Signs was the fact that throughout every step of the mural-making process, ProBlak’s hand was present.

“I think one of the (many, many) reasons why ProBlak’s mural is so deeply impactful is because it was painted by the artist who conceptualized it,” Kasabian said. “There’s something ineffable that gets transferred from the mind of an artist to a canvas that simply can’t be replicated by another painter because to them (a mural painter who is painting another artist’s artwork), it’s just a job.”

Members of the GN Crew (Left to Right: Soem, GoFive, and TakeOne) carefully sprayed over the charcoal lines created by pouncing with aerosol paint. Photo: Courtesy of Best Dressed Signs.

Her point makes me think about the importance of generating more opportunities for artists in Boston to work together rather than against one another in the industry. When we can recognize our strengths and are willing to ask for help from our peers, we have the power to create incredibly significant works of art—and even stronger communities. It’s why I feel so lucky to have been able to connect with Best Dressed Signs and the GN Crew in Jamaica Plain on that sunny April day, and why I believe Boston would benefit from more interdisciplinary collaboration among artists.

“Collaborating with the GN crew was so inspiring and meaningful for us—not only because of the level of mastery that they each bring to the project but also being able to witness how much they inspire and uplift other artists and the community as a whole.”

When I look up at the mural now, I’m most drawn to the figure’s twinkling eyes. Like a North Star in the center of the city, BREATHE LIFE TOGETHER is a personal reminder of what great feats can be accomplished when we approach new situations with an open heart and mind. It’s a calling to gather—a calling to be present, here, now. When we work together, especially as artists, we really do possess the power to create something beautiful.

Thank you to Meredith Kasabian and Josh Luke of Best Dressed Signs for taking the time to be present for an interview. Thank you to Soem, TakeOne, GoFive, and ProBlak for trusting me to help make such a stunning mural. Thank you to my Public Art team and Rachel Lake at the Greenway Conservancy for supporting my writing (and much more), and thank you to the Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts and Jenna Logue for providing me with the opportunity to work for The Greenway.

For more information about Kasabian, Luke, and their wonderful business, click here.

For more information about the GN Crew, click here.

Sophie Pollock is a multi-media artist based in Boston, Massachusetts. She received her B.F.A. in Studio Art from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and her B.A. in Psychology from Tufts University in 2021. She has been named a 2022 Tisch Summer Fellow, where she is currently working with the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy’s Public Art team to develop and install artworks throughout downtown Boston. For more information about Sophie, click here.

Summer workforce development opportunities on The Greenway are made possible with the generous support of Citizens.