The year is 2017. A small crowd gathers around a towering glass box in Auntie Kay & Uncle Frank Chin Park, myself, aged 16, among their ranks. Within its transparent home, blissfully unaware of its audience, a 3-D printer puts the finishing touches on a bright red rooster, having worked nonstop for hours on end. We wait with bated breath. The printer’s nozzle retreats, a metal bar nudges the newborn rooster to the edge of the 3-D printing platform, and the rooster plummets into a vending machine-like holding space with a clatter. From the crowd, several hands dart out. Cheers of triumph erupt as one comes away with the newly-minted prize, theirs to take home and cherish, no doubt. The 3-D printer has already begun laying the groundwork for the next rooster.

Over the course of a year, Chris Templeman’s installation Make and Take (colloquially known as Year of the Rooster) churned out over 2,000 3-D printed roosters. Templeman, in collaboration with New American Public Art, envisioned a piece that would speak to the ability of new technologies to democratize manufacturing and art. The design of the rooster was adapted from 3-D scanning a porcelain artifact from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. By 3-D printing replicas of the artifact for members of the public to take home with them, that art is able to transcend the realm of galleries and museum display cases and become whatever the taker wants it to be. Desk decor, a children’s toy, a board game piece – the possibilities are endless.

At 16 years old, I wanted one of those 3-D printed roosters SO bad. I hounded the installation every chance I got, often visiting several times a week. Alas, it was not in the cards for me. While Make and Take never gave me a 3-D printed rooster, it did open my eyes to the idea that public art could be participatory, democratic, and generative.

My views on public art continued to grow and develop when I was invited to participate in a workshop for artist Risa Puno’s 2018 installation Year of the Dog as a member of the Asian Community Development Corporation (ACDC)’s youth program, A-VOYCE (Asian Voices of Organized Youth for Community Empowerment). As a part of the visioning process for the piece, artist Risa Puno asked us (in addition to other members of the Chinatown community) what our favorite places, memories of, and things to do in Chinatown were. I remember writing a bunch of loose thoughts on sticky notes and placing them on sheets of poster paper. At the time, I didn’t quite understand what these things had to do with the art installation Risa was dreaming up, but I was happy to help however possible.

When the art piece was finally installed, I remember how excited I was to get to play with the blocks, spinning them around to form new words and meanings. But upon closer inspection, I was shocked to find my own memories of Chinatown, in my own handwriting, engraved onto some of the blocks, along with those of dozens of other community members. “I used to come here w/ my grandma all the time as a kid […] Now she has Alzheimer’s and will eventually forget about me, but I’ll always remember her and our memories in Chinatown.” “Dim sum with family → eating foods that remind me of home. Cha siu bao for comfort.” “Chinatown is where my heart is. It’s my home.” Reading through them, I was plunged into warm scenes of grocery shopping with parents on a Sunday morning, eating dim sum at a restaurant that no longer exists, playing kickball, singing karaoke.

Through engaging with Year of the Dog, I learned that while art can be playful, it can also be assertive. Art can be grounded in community and, in turn, ground the community. By centering the collective memory and experiences of the Chinatown community, Year of the Dog reminded us that Chinatown isn’t just a piece of land. En masse, the individual memories highlighted in this artwork remind us that Chinatown is a place rich in history and culture where people live, work, and play. At the heart of Chinatown, there are people. And that makes it a lot harder to justify building more luxury condos that would raise rents around the neighborhood and displace lower income residents. It makes it a lot easier to justify constructing more affordable housing to keep Chinatown residents in Chinatown. Public art is political.

Last June, I moved back to Boston after graduating from Brown University with a Bachelor’s in Environmental Science and Urban Studies. While I loved my time in Providence, there was never a doubt in my mind that I belonged in Boston. The four years I was gone felt like a lifetime, and I couldn’t wait to reground myself in the places and communities that so shaped me. So when the opportunity to work at The Greenway presented itself early in the summer, I jumped on it. Who wouldn’t want to work for the team that brought us Make and Take and Year of the Dog? Did I have any formal background or training in visual arts? No. But I was interested in continuing to explore the relationship between public art and the communities they are sited in, particularly Chinatown. And, of course, I was also excited about the opportunity to (re)connect with the various Boston-area community/arts/environmental organizations that working for the Greenway would bring me into contact with.

This summer, I had the pleasure of working with artist Ponnapa Prakkamakul on her forthcoming installation with the Greenway, Year of the Dragon. Year of the Dragon, a continuation of The Greenway’s Chinese Zodiac series, will be installed at Auntie Kay and Uncle Frank Chin Park in February 2024, just in time for the Lunar New Year. Through this piece, Ponnapa seeks to celebrate the strength and resilience of the Chinatown community by centering play and joy amidst the challenges of gentrification. When I first saw the initial renderings of Ponnapa’s project and it finally sunk in that this was something that I would get to be a part of, I felt giddy. This nourished the part of me that hounded Make and Take for a full year, that stood in the rain and read every block of Year of the Dog. And as a dragon myself (a 2000 baby!), this project felt particularly resonant.

As a part of the participatory design and visioning process, Ponnapa led a series of co-creation workshops to collect stories from diverse communities in Chinatown and include them as part of the artwork. Unlike dragons in the Western canon, which are typically characterized as greedy, fire-breathing tyrants (think Smaug from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit), dragons in Chinese mythology are benevolent creators and protectors associated with rain, wind, and bodies of water. Of the twelve animals that make up the Chinese zodiac, the dragon is the only one that does not actually exist. Because of this, our concept of what a dragon looks like has been pieced together from the most majestic elements of other animals, like the horns of a deer or the shimmering scales of a carp.

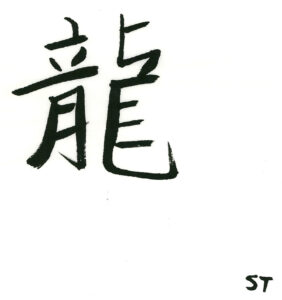

Through these co-creation workshops, Ponnapa sought to create a dragon that was unique to Boston’s Chinatown. Some of these took the form of calligraphy workshops, where community members (primarily elders) brainstormed qualities they associate with dragons and learned how to write those characters from local traditional calligraphy artist Judy Wong. These characters, in the handwriting of residents, will be laser-cut onto the final art piece.

Other workshops (geared primarily towards youth) had participants envision what their version of a dragon would look like and work collaboratively to design and fabricate an inflatable one, with the designs and the stories behind them informing the design of the final piece. And in one of those blatantly full-circle moments, I got to help out at a co-workshop with the current cohort of ACDC’s A-VOYCE youth, watching them participate in the creation of a work of public art and learn, as I had five years ago with Year of the Dog, that while public art can be beautiful and playful, it can also be a uniquely powerful expression of a community’s history, culture, and hopes for the future, anchoring a community both physically (“this is Chinatown”) and figuratively (“here’s why that is important”).

Susan Tang is the Rose Kennedy Greenway Conservancy’s Curatorial and Communications Fellow.

Summer workforce development opportunities on The Greenway are made possible with the generous support of Citizens.